Thirty Days to Freedom

When I’m in front of a group of athletes, teaching basic barbell movements, the nuances of the sprint, or proper kipping technique, I’m an expert. I tell them what I know, and I hold it out there as gospel. They usually become better athletes for it, and it makes me very happy.

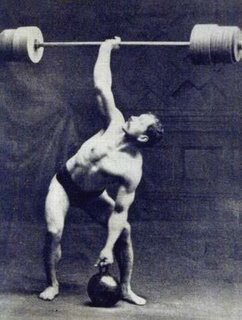

Still, it turns out that I don’t know a damn thing. When I hit the platform to clean and jerk or throw up a few snatches, I feel like an utter and complete novice. When I set my back on the bench for a few presses, I feel as weak as the first time I set foot in a gym. I attempted a one-legged squat the other day, and I would’ve fallen on my ass if I wasn’t holding onto the pull-up bar uprights.

I get a similar feeling when I read the works of the masters. I’m not talking about Milton, Moliere, and Shakespeare. I’m talking about the guys who have been slinging iron and pounding plywood longer than I’ve been alive—Mark Rippetoe, Glenn Pendlay, John Drewes, and Bill Starr make me feel downright slow.

These men have accumulated decades of training wisdom, the type borne of witnessing tens of thousands of attempts, and they have the wherewithal to get their observations down on paper. When I read these treatises on lifting, I hope to absorb a tenth of what’s there, knowing that I’ll probably have to settle for less. Without tens of thousands of observations of my own, I can’t fully assimilate their knowledge.

These men made a commitment to strength training that I cannot match while working a nine to five.

So be it. In the name of progress, I’ve handed in my resignation. I’m trading a 401(k) and dental coverage for financial uncertainty and a shot at becoming a veteran of the iron game. Starting June 1st, I will be a full-time trainer, author, equipment vendor, and business manager, taking up a station in the back offices of Crossfit Boston.

With the blessing of my girlfriend, a $400 plane ticket, and a pair of lifting shoes, I’ll spend my first week on the job at the U.S. Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, taking the preliminary steps toward a USAW Club Coach Certification. It seems like as decent a start as any.

I don't have decades of time under the bar, but I’m working on it. In twenty years, I may stand in front of a group of athletes and actually know what I’m talking about. That’ll be a good day.

Go faster!

Picture of Coach Rip with Nicole Carroll, courtesy of Crossfit Eastside.

When I’m in front of a group of athletes, teaching basic barbell movements, the nuances of the sprint, or proper kipping technique, I’m an expert. I tell them what I know, and I hold it out there as gospel. They usually become better athletes for it, and it makes me very happy.

Still, it turns out that I don’t know a damn thing. When I hit the platform to clean and jerk or throw up a few snatches, I feel like an utter and complete novice. When I set my back on the bench for a few presses, I feel as weak as the first time I set foot in a gym. I attempted a one-legged squat the other day, and I would’ve fallen on my ass if I wasn’t holding onto the pull-up bar uprights.

I get a similar feeling when I read the works of the masters. I’m not talking about Milton, Moliere, and Shakespeare. I’m talking about the guys who have been slinging iron and pounding plywood longer than I’ve been alive—Mark Rippetoe, Glenn Pendlay, John Drewes, and Bill Starr make me feel downright slow.

These men have accumulated decades of training wisdom, the type borne of witnessing tens of thousands of attempts, and they have the wherewithal to get their observations down on paper. When I read these treatises on lifting, I hope to absorb a tenth of what’s there, knowing that I’ll probably have to settle for less. Without tens of thousands of observations of my own, I can’t fully assimilate their knowledge.

These men made a commitment to strength training that I cannot match while working a nine to five.

So be it. In the name of progress, I’ve handed in my resignation. I’m trading a 401(k) and dental coverage for financial uncertainty and a shot at becoming a veteran of the iron game. Starting June 1st, I will be a full-time trainer, author, equipment vendor, and business manager, taking up a station in the back offices of Crossfit Boston.

With the blessing of my girlfriend, a $400 plane ticket, and a pair of lifting shoes, I’ll spend my first week on the job at the U.S. Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, taking the preliminary steps toward a USAW Club Coach Certification. It seems like as decent a start as any.

I don't have decades of time under the bar, but I’m working on it. In twenty years, I may stand in front of a group of athletes and actually know what I’m talking about. That’ll be a good day.

Go faster!

Picture of Coach Rip with Nicole Carroll, courtesy of Crossfit Eastside.