Finding the Switch

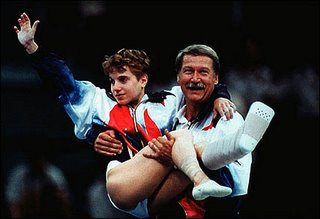

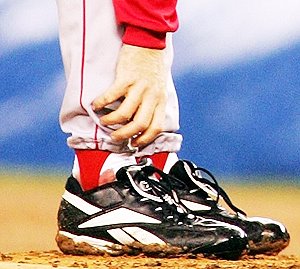

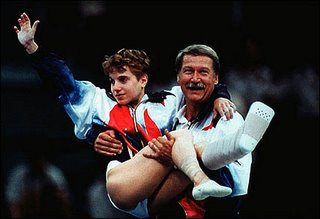

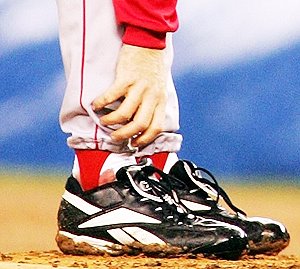

The human body is capable of amazing things. In the past few years, we’ve seen spectacular demonstrations of will—Lance Armstrong winning seven consecutive Tours after a crippling battle with cancer, Curt Shilling blowing out the Yankees in the 2004 ALCS with a bloody sock and a stapled tendon, Kerri Strug landing a gold-medal winning vault in the 1996 Summer Games with a sprained ankle.

We call these performances heroic. Mention “Lance” or “Shill” to any casual sports fan, and they know exactly who you’re talking about. They’ve entered our collective unconscious as heroes, because they were exceptional—strong and unrelenting, they blocked out pain and fatigue to achieve greater glory. We know that lesser athletes would’ve failed, trailing off the lead, hitting the showers early.

They didn’t, and we idolize them for it.

These athletes have a special gift. They know that the limits of human performance are dictated only by the mind, and they tap into this realization to overcome the trivialities of pain, oxygen deprivation, and lactic acid buildup. When the body begs to quit, their minds say “No!”, and the Switch is flipped.

Last night, I was training a client. Halfway into the workout, he stood beneath the pull-up bar, hands on his knees, sucking big gulps of air, and showing no signs of forward progress.

I told him to get back on the bar. We were training the Switch.

He kept going. Finishing the workout a few minutes later, he collapsed off the rower with a familiar mixture of relief and exhaustion. He’d pushed through his body’s protestations, seeing the workout to its end.

The ability to will your body onward through adversity creates athletic monsters. The difference between first and last place in a Crossfit workout doesn’t depend on exercise speed—it depends on how long you rest during the effort.

I’ve watched the video of Greg and Annie pushing through Fran upwards of ten times, trying to decipher the secret of their 2:47 performance. It’s not the speed of movement, (although this does play a part). It’s the lack of rest.

They just don’t stop.

Don’t make the mistake of thinking they’re so damn fit that they’re not winded. Fran isn’t a walk in the park for anyone, these guys included. They work within the same general physical limitations as the rest of us.

Like Lance, Shill, and Strug, these athletes have superb control over the Switch. When their bodies threaten to quit, they turn a deaf ear. They’ve refined this capability at ever-increasing levels of fatigue, making the Switch an instinctual response.

At first, the Switch requires conscious effort. As you stand beneath the pull-up bar, seemingly incapable of another rep, go ahead and get on the bar. Do it before you think you’re ready.

It doesn’t involve too much coherent thought. Just go.

To find your Switch, you need to eliminate the idea of personal incapability from your thoughts. If your body fails you, so be it, but don’t let your mind be the source of your limitations. Don’t think “I can’t.”

Think “I will.”

Practice this. Once a workout, keep going when you want to stop. As you accumulate experience flipping the Switch, the process will become automatic. You’ll rest much less, and your workout times will go through the roof.

In essence, you’ll trick your body’s defense mechanisms into remission. With time, they won’t kick in as easily, and you’ll work harder and longer. Your fitness will reflect your increased power output.

Go ahead. Flip the Switch. You can thank me later.

Picture of Kerri Strug courtesy of Herald-Sun.com. Shilling's ankle courtesy of Si.com. Stop by tomorrow for the first look at this Sunday's Again Faster Weekend Workout. It'll be good. I promise.

Picture of Kerri Strug courtesy of Herald-Sun.com. Shilling's ankle courtesy of Si.com. Stop by tomorrow for the first look at this Sunday's Again Faster Weekend Workout. It'll be good. I promise.

The human body is capable of amazing things. In the past few years, we’ve seen spectacular demonstrations of will—Lance Armstrong winning seven consecutive Tours after a crippling battle with cancer, Curt Shilling blowing out the Yankees in the 2004 ALCS with a bloody sock and a stapled tendon, Kerri Strug landing a gold-medal winning vault in the 1996 Summer Games with a sprained ankle.

We call these performances heroic. Mention “Lance” or “Shill” to any casual sports fan, and they know exactly who you’re talking about. They’ve entered our collective unconscious as heroes, because they were exceptional—strong and unrelenting, they blocked out pain and fatigue to achieve greater glory. We know that lesser athletes would’ve failed, trailing off the lead, hitting the showers early.

They didn’t, and we idolize them for it.

These athletes have a special gift. They know that the limits of human performance are dictated only by the mind, and they tap into this realization to overcome the trivialities of pain, oxygen deprivation, and lactic acid buildup. When the body begs to quit, their minds say “No!”, and the Switch is flipped.

Last night, I was training a client. Halfway into the workout, he stood beneath the pull-up bar, hands on his knees, sucking big gulps of air, and showing no signs of forward progress.

I told him to get back on the bar. We were training the Switch.

He kept going. Finishing the workout a few minutes later, he collapsed off the rower with a familiar mixture of relief and exhaustion. He’d pushed through his body’s protestations, seeing the workout to its end.

The ability to will your body onward through adversity creates athletic monsters. The difference between first and last place in a Crossfit workout doesn’t depend on exercise speed—it depends on how long you rest during the effort.

I’ve watched the video of Greg and Annie pushing through Fran upwards of ten times, trying to decipher the secret of their 2:47 performance. It’s not the speed of movement, (although this does play a part). It’s the lack of rest.

They just don’t stop.

Don’t make the mistake of thinking they’re so damn fit that they’re not winded. Fran isn’t a walk in the park for anyone, these guys included. They work within the same general physical limitations as the rest of us.

Like Lance, Shill, and Strug, these athletes have superb control over the Switch. When their bodies threaten to quit, they turn a deaf ear. They’ve refined this capability at ever-increasing levels of fatigue, making the Switch an instinctual response.

At first, the Switch requires conscious effort. As you stand beneath the pull-up bar, seemingly incapable of another rep, go ahead and get on the bar. Do it before you think you’re ready.

It doesn’t involve too much coherent thought. Just go.

To find your Switch, you need to eliminate the idea of personal incapability from your thoughts. If your body fails you, so be it, but don’t let your mind be the source of your limitations. Don’t think “I can’t.”

Think “I will.”

Practice this. Once a workout, keep going when you want to stop. As you accumulate experience flipping the Switch, the process will become automatic. You’ll rest much less, and your workout times will go through the roof.

In essence, you’ll trick your body’s defense mechanisms into remission. With time, they won’t kick in as easily, and you’ll work harder and longer. Your fitness will reflect your increased power output.

Go ahead. Flip the Switch. You can thank me later.

Picture of Kerri Strug courtesy of Herald-Sun.com. Shilling's ankle courtesy of Si.com. Stop by tomorrow for the first look at this Sunday's Again Faster Weekend Workout. It'll be good. I promise.

Picture of Kerri Strug courtesy of Herald-Sun.com. Shilling's ankle courtesy of Si.com. Stop by tomorrow for the first look at this Sunday's Again Faster Weekend Workout. It'll be good. I promise.

1 Comments:

Pretty sure I took that picture, Dave ;)

Oh, you mean Tara...

Post a Comment

<< Home