Peter’s Kill and The Lost City

We woke up at 4:30 on Saturday morning, leaving the sanctuary of home for the biting cold of pre-dawn October.

We loaded ropes, harnesses, and packs into the back of the car. I was headed for paradise, traveling along side John, Marcia, Sam, and Nick.

The caffeine obliterated any thoughts of sleep as I hacked at my laptop, calling up images of our last visit to the Shawangunks. Pictures of gorgeous gray fault-block and a cobalt blue sky flashed across the screen. Sam and I looked through every picture in my library, recalling a summer’s worth of workouts and climbs.

Every click was met with a new image of friends and family. Again Faster suffer-fests, Crossfit Boston’s new digs, outings to the Quincy Quarry—a lifetime’s worth of adventure condensed to six months of photos.

The hard colors of the city melted into reds and browns as we drove west, speeding through a pink dawn toward New York. Unable to concentrate on my writing, I gazed out the window at the emerging day, Sam half-asleep on my right shoulder. The sun was bright and constant, promising everything I’d come to expect from our trips to the Gunks.

We turned off the New York State Thruway just before eight o’clock. The Near Trapps loomed over Route 44, inspiring a sense of majesty and awe. We drove under the access bridge, foregoing the Mohunk Reservation for a path less traveled.

Just southwest of the Trapps, Minnewaska State Park holds Peter’s Kill, a lesser known cliff band buried in the bright deciduous forest. Unloading our gear, we layered thermal underwear under heavy fleece jackets to fight the breeze.

Sunshine erupted from behind gray clouds as we moved into the forest, offering a respite from the cold. By the time we reached the base of the cliff we had shed our outerwear, enjoying the natural windbreak of the dense underbrush.

John had gone ahead to set our anchors, and we scrambled along the base of the cliff looking for signs of our leader. Nick dropped a case of water along the path, forcing him to stop. As I called for him to hurry up, John bellowed from the top of the wall:

“Rope!”

Two gray strands fell from the sky, hitting the ground a few feet from Nick’s location. Fortune had guided us in.

I pulled on my harness and pumped my feet into my rock shoes, smiling at the sound of their vacuum fit making good contact with my heel. The rush of escaping air held the promise of solid footholds all day long.

I tied in at the bottom of “Captain’s Log”, threading the rope through my harness. The 5.4 climb was riddled with horizontal cracks, providing a nice start to the day. My holds were secure as I scaled the face, my movements slow and easy. The anchor came quickly, and I was lowered to the forest floor unscathed.

The second climb of the day was significantly more daunting, a 5.7 route with a tricky crux move. "Kling-On" starts with an irresistible overhanging ledge about six and a half feet off the ground. In a nod to my Crossfit training, I kipped into the ledge, a hard pull catapulting me to support on top of the rock. I stood up and surveyed the remaining face.

Three-quarters of the way up, a block of white rock bulges over the route. It requires the climber to make a non-intuitive move, shifting into the corner to secure a left foothold before going up and over.

I lost my grip three times at the apex of the climb, saving a fall only through some very lucky reach-and-slap attempts at a deep, shelf-like handhold just above the crux. My heart was hammering as Sam brought me down, my nervous system refusing to acknowledge the safety afforded by the top-rope.

On the ground, I watched Marcia tackle “Under Kling-On”, a 5.9 rated route that starts hot and heavy and ends with a whimper. The second move is a contortionist’s nightmare, asking the climber put left knee to chin in order to secure a foothold across the rock. This is a stretchy, physically demanding move, but it comprises the entire challenge of “Under Kling-On”. We each completed the route quickly, a bunch of 5.7-5.8 climbers smoking a 5.9 climb. We wondered, loudly, as to the adequacy of the rating.

Like most gymnastic performances, a climb is remembered (and rated) for its hardest move, the rest of the route cast into obscurity.

While Sam, Nick, and I took turns climbing the Trekkie wall, John had negotiated the use of another party’s gear. “Reach Around” was just around the corner to the climber’s left, a pumpy sixty-foot route replete with two overhangs and a nasty crux move. It's a sustained pitch, and very hard on the arms.

I belayed for Marcia as she moved to the crux, a right-facing overhang with a blind handhold to the inside. Unable to perceive the route, Marcia traversed right to a blank face, frustrated at the lack of holds.

“What the hell are you doing? Get back over there!”

My gentle encouragement did the trick, and Marcia moved left and through the overhang with minimal effort. After some contemplation she made the final move over a smaller roof to the anchor, ending a solid half-hour of climbing.

I tied in for the same climb, confident of my ability to make the top. Ten feet up the book, I realized the climb was not going to be an afternoon stroll. All hands and no feet, I pulled my way to the crux, grabbing a juggy hold just inside the dihedral. Securing my right, I threw my left hand to the top of the overhanging formation. Gripping hard, I cast my other hand up and pulled over the crux.

Standing on the ledge, my arms were shaking uncontrollably. I joked with the climbers on the ground, waiting for the tremors to stop. They did, but I was too spent to continue. After several attempts at the final move, I asked John to bring me back down.

It would be the only climb that beat me, a 5.7 with an obvious finish. The next climber stood in the same spot I had, perplexed by the ending sequence. I told him how it went, teaching a move I’d been unable to complete.

“There’s a left-facing flake with a great thumb. Pull on it and put your right hand in the horizontal crack below the roof. You’ve got to do it fast.”

I’d failed because of hesitation, conducting an impromptu experiment in prolonged isometric holds. Not surprisingly, gravity lasted longer than my grip, and I fell off the wall. The climber made the anchor.

John climbed the face next, moving up and around the overhang with little fuss. Like Olympic lifting, technique is the primary determinant of success in rock climbing. Physical condition takes a back seat to coordination, agility, and accuracy, traits developed through practice. John’s decades of experience on rock have given him these traits.

Abandoning “Reach Around”, we moved east. “TP” and “Genuflect” are perfectly parallel, located on opposite sides of a small box canyon to the right of “Under Kling-On”. The stone forms ninety degree angles everywhere, exhibiting symmetry out of place with the bramble of the surrounding forest.

Both climbs warrant a 5.6 rating, rewarding the patient climber with adequate holds all the way to the top. After a moderately difficult start, “TP” devolves into a ladder of horizontal cracks. It was a nice break from the grip workout of “Reach Around”, and I felt fluid and relaxed for the entire climb.

Genuflect is similarly perfunctory and unmemorable, a thirty foot fault-to-crack climb with no awkward moves. One by one, we polished off the wall, clearing our gear to seek a new challenge.

While Marcia, Sam, and Nick packed up, John and I hiked down the Peter’s Kill Trail, ropes and slings in tow.

We went a quarter mile west, scrambling to the top of a low face to secure two top-ropes. “Left Block” and “Right Block” were aptly named, two cracks in a stack of gray fault block on top of a mound of fallen rock. With “Seams Like Fun”, the three routes ranged from 5.4 to 5.8, progressing in difficulty from left to right. We ran static-to-sling anchors above “Right Block” and “Seams”, leaving “Left Block” unclimbed.

Sundown comes early in the forest. The sun descended through the tree line as we climbed the short routes, bringing a forgotten chill back to the wall. We climbed in the waning light, hands and feet sore from the demands of the day.

Sitting on a large rock, Sam and I ate a Spartan dinner of macadamia nuts and protein powder, our outerwear pulled from our backpacks. The red, green, and gold of the forest took a dull sheen, and the sky turned from bright blue to grey. We moved to leave Peter’s Kill, a monumental day of climbing behind us.

We reclaimed our equipment from the block, cramming ropes and leads into impossibly small bags. Two hundred feet of hiking put us back in the parking lot, face-to-face with the first signs of civilization we’d seen in over eight hours.

Gridlock traffic greeted our trip back to New Paltz, a reminder that our choice of venue was well-informed. Hundreds of cars stretched to the horizon, taillights blinking, yet we had only seen one other group all day.

An hour later we were gathered around a table at Barnaby’s, celebrating Nick’s birthday with steaks and a round of Oktoberfest. Relaxed and thoroughly spent, we made a fateful choice.

“Tomorrow, we can go back where we were, or we can go to another place. You have to hike to get there. The Lost City.”

John’s pronouncement was understated, but we understood the implication right away. Of course we would hike—the mere thought of a place called “The Lost City” smacked of adventure. We decided without dissent, finishing our meal under the soft lights, wondering what The Lost City held in store.

The next morning we hiked toward our destination, no more knowledgeable than we were the night before. The thin, grey cover of dawn had given way to bright sunshine, illuminating the forest in a wave of yellow and brown. The High Peter’s Kill Trail turned to bog, our walk restricted to a twelve-inch wide platform over the muck. We traversed a stream, leaving the lowland water for a thick carpet of leaves.

King’s Lane continued upward into the forest, a wide thoroughfare through the trees. John stopped in the middle of the trail, gesturing off into the woods.

We would hike in without a discernable path—The Lost City was directly North.

The smooth expanse of leaves gave way to large boulders, densely packed on the forest floor. They ranged in size from filing cabinets to buildings, closer and closer together as we moved up the hill.

My pack slowed me significantly, 50-plus pounds of rope and water tugging ceaselessly at my back. The cliff came into view as I crested a huge formation of fallen block, appearing almost white in the intense sunlight.

I dropped my load with relief, waiting for the others to catch up. Reassembled, all five of us headed for the cliff-top, crawling through a cave-like structure to access a thin pass up the side of the face. Wearing rubber-soled Adidas, I checked every foothold before placing my weight, my pulse racing at the thought of a hard fall.

A breathtaking view awaited us at the top, the autumn foliage extending to the horizon without interruption. It was unquestionably gorgeous, the type of sight that makes a man feel totally and utterly insignificant.

We set two anchors as a front blew in from the West. The sun appeared in fits and starts, the temperature alternately climbing and plummeting with each passing cloud. I was glad for my thermal layers as we descended, my fingers growing cold in the morning air.

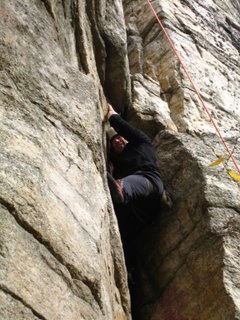

Our climbs were unnamed, the product of a local desire to keep The Lost City lost. The left-most climb was a combination corner and crack, while the right-most climb was a deep fault that persuaded the climber to move ever-further into its folds.

John, Marcia, and Nick took turns on the corner route while Sam and I scaled the rightward climb. Sam tied into the rope, shedding her jacket in anticipation of a difficult effort.

The first ascent of the day is always taxing, and Samantha moved slowly up the rock. She was intermittently swallowed and released by the yawning gap in the cliff, finding holds anywhere she could.

She made the anchor without a fall, pausing at the top to take in the view behind her. I lowered her hesitantly, giving her time to negotiate the tricky lines of the rappel.

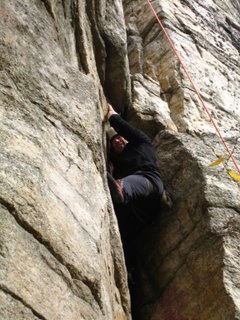

Back on the ground, we switched roles. With Sam belaying, I buried myself in the climb. I wedged further and further into the cliff as I moved upward, relieved at the relative safety of the rock’s embrace. Negotiating the climb required me to shift my weight constantly, seeking hand and foot holds on both sides of the fault. I pumped hard with my arms, pulling against the sharp rock.

The silver glint of the anchor came into view, and I called to be lowered without surveying the scene around me. I immediately regretted my oversight, resolving to bring my camera to the top on the next climb.

Nick was coming off the corner when Sam and I wandered over. The sky was clear and endless above his head, strikingly beautiful against the bright yellow leaves of a nearby tree.

The route was deceptively difficult, hard despite the help provided by the square intersection of two sections of rock. The top of the pitch was slightly past vertical, demanding repeat pull-ups to make the anchor. Despite a year of climbing, I hadn’t yet learned to optimize my footholds, and my arms were paying the price.

Standing on a ledge at the top, I turned to take a picture, pulling my small digital camera from its holster. The trees went forever, dappled with sunlight in a two-hundred degree panorama. My leg vibrated against the rock as I recorded the scene, my muscles refusing to relax on my high perch.

Directly ahead, the backside of the Trapps was silhouetted against the clouds, a small depression indicating the path of Route 44 through the Shawnagunks. We'd left behind every sign of man's influence, save this notch.

John set a new anchor thirty feet left of our second climb.

From ten feet back, the face had a single, lonely crack and no discernable footholds. I walked up to the rock, unbelieving. Sure enough, a climb materialized—a ridge on the right, a skinny foothold on the left, and a long reach to safety.

Sam and I stood at the bottom, choreographing every move, positive that we were looking at the hardest climb of the day.

She pushed her hands into the crack, making her first move toward the top. Ironically, the penalty for a fall is higher when the climber is closer to the ground—due to rope stretch, a three-foot drop could result in a broken ankle.

She fell on her second move, hitting the ground feet-first and unhurt. We went over the sequence again, and Sam climbed. She cleared the second move, planting her right foot on an all-day ledge to the right of the crack. Knuckle-deep, she pulled upward.

Her foot slipped off a tenuous left-foot hold, and gravity took over. Weighting the rope, she leaned back from the face and pressed her back against a tree, relieving the accumulated strain on her arms and legs.

The third move beat her several times, each attempt forcing her to clamor into position for the difficult reach once again. Frustrated, she leaned against the tree, ripping her jacket off and staring intently at the rock.

She cranked through the opening moves on her fourth attempt, finding a new handhold slightly higher than her last elevation. A juggy right hand, the hold boosted her up to the first ledge and a long-awaited rest.

The unnamed route was unrelenting. Sparse holds required Sam to crack-climb, a type of climbing her amorphous slippers weren’t made to handle. Noticing the truncated corner configuration of the rock, I suggested she perform a layback, pinning her feet to the left-hand face with her arms fully extended.

This did the trick. Sam pulled through the rest of the lengthy route, plodding through ten meters of energy-sapping ascent. She grunted as she climbed, her exclamations a product of extreme exertion.

On the ground, she shook her hands out, angry at the difficulty of the climb.

Ten minutes later I attempted it, failing in many of the same spots. The first four moves drained my pulling power as I grabbed for the ledge over and over again. The layback reduced my already-fatigued arms to a mass of quivering tendons, my grip junked by the sharp crystals inside the crack. Groaning and grunting, I made the anchor, five or six falls marring the attempt.

My knuckles bleeding, I proposed we name the route. This honor is typically reserved for the first person to complete a pitch, but I’ve never been one to stand on decorum.

The sequence of events drove the nomenclature—“Tree Lean and Groan” was born. Nine days after the experience, my knuckles still bear the marks of that climb, pink and raw across the back of my hand.

Nick beat the hell out of "Tree Lean". He is enormous for a rock climber, tipping the scales at over 200 pounds. Despite his size, Nick has tons of strength, and the prolonged layback suited his abilities perfectly.

With almost no hesitation, Nick cranked up the route, topping out in half the time it had taken Samantha and I. With a mixture of awe and envy, I cheered Nick's tremendous effort, clapping as John lowered him to the ground.

We finished our adventure in The Lost City with an easy climb, scaling a cold corner of the face with minimal effort, enjoying a respite from the mental and physical trials of the day's earlier climbs.

Sam and I packed our ropes and slings, lingering to watch a young German woman attempt a difficult climb. She moved gracefully up the slick rock, holding onto thin air as she flew upward. Her route was easily a 5.10, far beyond our abilities.

My trance was broken as she fell, her belay rope snapping taut in the cold October dusk. We turned to leave, slinging on our packs for the hike back to civilization.

I concentrated on the boulders as we descended from the cliff, scrambling over and around mountains of fallen rock. It felt wrong to leave such a beautiful place--golden trees and a gorgeous blue sky promised that there would be other days like this, days where everything was perfect.

I moved purposefully but slowly, leaving The Lost City only out of necessity. Eventually the scree gave way to open forest, and we joined Nick, John, and Marcia on King's Lane.

We crossed the rushing stream, marking our passage from the dry highlands to the soggy wetland, stepping quickly across the wet stones. We moved single-file along the man-made catwalk, finally exiting to the parking lot at the base of the High Peter's Kill trail.

The weekend was epic, spanning twelve pitches over two days. I felt out of place as we drove east, the beauty of the Shawangunks giving way to the Berkshires giving way to concrete and gleaming metal. The hills receded as we approached the coast, zipping through the suburban enclaves of Wellesley and Newton, the wild plan of nature turning to the carefully-constructed schematics of man.

Reclining in a state of near-sleep, it struck me that I was fortunate to have such friends, folks who knew about the truly important places, places where time is only as important as your next adventure.

That night I fell asleep with a smile on my face, exhausted and elated from our journey. Crossfit was next on the agenda, and 4:30 promised to come quickly.

Go faster!

Ratings and names from the Peter's Kill area courtesy of "Peter's Kill Climbing Guide" by Robert Wilson and Jennifer Sauer. The Lost City is a figment of my imagination, and does not in fact exist. Looking for it is a waste of time, much like yoga or anything involving a Swiss ball.

We woke up at 4:30 on Saturday morning, leaving the sanctuary of home for the biting cold of pre-dawn October.

We loaded ropes, harnesses, and packs into the back of the car. I was headed for paradise, traveling along side John, Marcia, Sam, and Nick.

The caffeine obliterated any thoughts of sleep as I hacked at my laptop, calling up images of our last visit to the Shawangunks. Pictures of gorgeous gray fault-block and a cobalt blue sky flashed across the screen. Sam and I looked through every picture in my library, recalling a summer’s worth of workouts and climbs.

Every click was met with a new image of friends and family. Again Faster suffer-fests, Crossfit Boston’s new digs, outings to the Quincy Quarry—a lifetime’s worth of adventure condensed to six months of photos.

The hard colors of the city melted into reds and browns as we drove west, speeding through a pink dawn toward New York. Unable to concentrate on my writing, I gazed out the window at the emerging day, Sam half-asleep on my right shoulder. The sun was bright and constant, promising everything I’d come to expect from our trips to the Gunks.

We turned off the New York State Thruway just before eight o’clock. The Near Trapps loomed over Route 44, inspiring a sense of majesty and awe. We drove under the access bridge, foregoing the Mohunk Reservation for a path less traveled.

Just southwest of the Trapps, Minnewaska State Park holds Peter’s Kill, a lesser known cliff band buried in the bright deciduous forest. Unloading our gear, we layered thermal underwear under heavy fleece jackets to fight the breeze.

Sunshine erupted from behind gray clouds as we moved into the forest, offering a respite from the cold. By the time we reached the base of the cliff we had shed our outerwear, enjoying the natural windbreak of the dense underbrush.

John had gone ahead to set our anchors, and we scrambled along the base of the cliff looking for signs of our leader. Nick dropped a case of water along the path, forcing him to stop. As I called for him to hurry up, John bellowed from the top of the wall:

“Rope!”

Two gray strands fell from the sky, hitting the ground a few feet from Nick’s location. Fortune had guided us in.

I pulled on my harness and pumped my feet into my rock shoes, smiling at the sound of their vacuum fit making good contact with my heel. The rush of escaping air held the promise of solid footholds all day long.

I tied in at the bottom of “Captain’s Log”, threading the rope through my harness. The 5.4 climb was riddled with horizontal cracks, providing a nice start to the day. My holds were secure as I scaled the face, my movements slow and easy. The anchor came quickly, and I was lowered to the forest floor unscathed.

The second climb of the day was significantly more daunting, a 5.7 route with a tricky crux move. "Kling-On" starts with an irresistible overhanging ledge about six and a half feet off the ground. In a nod to my Crossfit training, I kipped into the ledge, a hard pull catapulting me to support on top of the rock. I stood up and surveyed the remaining face.

Three-quarters of the way up, a block of white rock bulges over the route. It requires the climber to make a non-intuitive move, shifting into the corner to secure a left foothold before going up and over.

I lost my grip three times at the apex of the climb, saving a fall only through some very lucky reach-and-slap attempts at a deep, shelf-like handhold just above the crux. My heart was hammering as Sam brought me down, my nervous system refusing to acknowledge the safety afforded by the top-rope.

On the ground, I watched Marcia tackle “Under Kling-On”, a 5.9 rated route that starts hot and heavy and ends with a whimper. The second move is a contortionist’s nightmare, asking the climber put left knee to chin in order to secure a foothold across the rock. This is a stretchy, physically demanding move, but it comprises the entire challenge of “Under Kling-On”. We each completed the route quickly, a bunch of 5.7-5.8 climbers smoking a 5.9 climb. We wondered, loudly, as to the adequacy of the rating.

Like most gymnastic performances, a climb is remembered (and rated) for its hardest move, the rest of the route cast into obscurity.

While Sam, Nick, and I took turns climbing the Trekkie wall, John had negotiated the use of another party’s gear. “Reach Around” was just around the corner to the climber’s left, a pumpy sixty-foot route replete with two overhangs and a nasty crux move. It's a sustained pitch, and very hard on the arms.

I belayed for Marcia as she moved to the crux, a right-facing overhang with a blind handhold to the inside. Unable to perceive the route, Marcia traversed right to a blank face, frustrated at the lack of holds.

“What the hell are you doing? Get back over there!”

My gentle encouragement did the trick, and Marcia moved left and through the overhang with minimal effort. After some contemplation she made the final move over a smaller roof to the anchor, ending a solid half-hour of climbing.

I tied in for the same climb, confident of my ability to make the top. Ten feet up the book, I realized the climb was not going to be an afternoon stroll. All hands and no feet, I pulled my way to the crux, grabbing a juggy hold just inside the dihedral. Securing my right, I threw my left hand to the top of the overhanging formation. Gripping hard, I cast my other hand up and pulled over the crux.

Standing on the ledge, my arms were shaking uncontrollably. I joked with the climbers on the ground, waiting for the tremors to stop. They did, but I was too spent to continue. After several attempts at the final move, I asked John to bring me back down.

It would be the only climb that beat me, a 5.7 with an obvious finish. The next climber stood in the same spot I had, perplexed by the ending sequence. I told him how it went, teaching a move I’d been unable to complete.

“There’s a left-facing flake with a great thumb. Pull on it and put your right hand in the horizontal crack below the roof. You’ve got to do it fast.”

I’d failed because of hesitation, conducting an impromptu experiment in prolonged isometric holds. Not surprisingly, gravity lasted longer than my grip, and I fell off the wall. The climber made the anchor.

John climbed the face next, moving up and around the overhang with little fuss. Like Olympic lifting, technique is the primary determinant of success in rock climbing. Physical condition takes a back seat to coordination, agility, and accuracy, traits developed through practice. John’s decades of experience on rock have given him these traits.

Abandoning “Reach Around”, we moved east. “TP” and “Genuflect” are perfectly parallel, located on opposite sides of a small box canyon to the right of “Under Kling-On”. The stone forms ninety degree angles everywhere, exhibiting symmetry out of place with the bramble of the surrounding forest.

Both climbs warrant a 5.6 rating, rewarding the patient climber with adequate holds all the way to the top. After a moderately difficult start, “TP” devolves into a ladder of horizontal cracks. It was a nice break from the grip workout of “Reach Around”, and I felt fluid and relaxed for the entire climb.

Genuflect is similarly perfunctory and unmemorable, a thirty foot fault-to-crack climb with no awkward moves. One by one, we polished off the wall, clearing our gear to seek a new challenge.

While Marcia, Sam, and Nick packed up, John and I hiked down the Peter’s Kill Trail, ropes and slings in tow.

We went a quarter mile west, scrambling to the top of a low face to secure two top-ropes. “Left Block” and “Right Block” were aptly named, two cracks in a stack of gray fault block on top of a mound of fallen rock. With “Seams Like Fun”, the three routes ranged from 5.4 to 5.8, progressing in difficulty from left to right. We ran static-to-sling anchors above “Right Block” and “Seams”, leaving “Left Block” unclimbed.

Sundown comes early in the forest. The sun descended through the tree line as we climbed the short routes, bringing a forgotten chill back to the wall. We climbed in the waning light, hands and feet sore from the demands of the day.

Sitting on a large rock, Sam and I ate a Spartan dinner of macadamia nuts and protein powder, our outerwear pulled from our backpacks. The red, green, and gold of the forest took a dull sheen, and the sky turned from bright blue to grey. We moved to leave Peter’s Kill, a monumental day of climbing behind us.

We reclaimed our equipment from the block, cramming ropes and leads into impossibly small bags. Two hundred feet of hiking put us back in the parking lot, face-to-face with the first signs of civilization we’d seen in over eight hours.

Gridlock traffic greeted our trip back to New Paltz, a reminder that our choice of venue was well-informed. Hundreds of cars stretched to the horizon, taillights blinking, yet we had only seen one other group all day.

An hour later we were gathered around a table at Barnaby’s, celebrating Nick’s birthday with steaks and a round of Oktoberfest. Relaxed and thoroughly spent, we made a fateful choice.

“Tomorrow, we can go back where we were, or we can go to another place. You have to hike to get there. The Lost City.”

John’s pronouncement was understated, but we understood the implication right away. Of course we would hike—the mere thought of a place called “The Lost City” smacked of adventure. We decided without dissent, finishing our meal under the soft lights, wondering what The Lost City held in store.

The next morning we hiked toward our destination, no more knowledgeable than we were the night before. The thin, grey cover of dawn had given way to bright sunshine, illuminating the forest in a wave of yellow and brown. The High Peter’s Kill Trail turned to bog, our walk restricted to a twelve-inch wide platform over the muck. We traversed a stream, leaving the lowland water for a thick carpet of leaves.

King’s Lane continued upward into the forest, a wide thoroughfare through the trees. John stopped in the middle of the trail, gesturing off into the woods.

We would hike in without a discernable path—The Lost City was directly North.

The smooth expanse of leaves gave way to large boulders, densely packed on the forest floor. They ranged in size from filing cabinets to buildings, closer and closer together as we moved up the hill.

My pack slowed me significantly, 50-plus pounds of rope and water tugging ceaselessly at my back. The cliff came into view as I crested a huge formation of fallen block, appearing almost white in the intense sunlight.

I dropped my load with relief, waiting for the others to catch up. Reassembled, all five of us headed for the cliff-top, crawling through a cave-like structure to access a thin pass up the side of the face. Wearing rubber-soled Adidas, I checked every foothold before placing my weight, my pulse racing at the thought of a hard fall.

A breathtaking view awaited us at the top, the autumn foliage extending to the horizon without interruption. It was unquestionably gorgeous, the type of sight that makes a man feel totally and utterly insignificant.

We set two anchors as a front blew in from the West. The sun appeared in fits and starts, the temperature alternately climbing and plummeting with each passing cloud. I was glad for my thermal layers as we descended, my fingers growing cold in the morning air.

Our climbs were unnamed, the product of a local desire to keep The Lost City lost. The left-most climb was a combination corner and crack, while the right-most climb was a deep fault that persuaded the climber to move ever-further into its folds.

John, Marcia, and Nick took turns on the corner route while Sam and I scaled the rightward climb. Sam tied into the rope, shedding her jacket in anticipation of a difficult effort.

The first ascent of the day is always taxing, and Samantha moved slowly up the rock. She was intermittently swallowed and released by the yawning gap in the cliff, finding holds anywhere she could.

She made the anchor without a fall, pausing at the top to take in the view behind her. I lowered her hesitantly, giving her time to negotiate the tricky lines of the rappel.

Back on the ground, we switched roles. With Sam belaying, I buried myself in the climb. I wedged further and further into the cliff as I moved upward, relieved at the relative safety of the rock’s embrace. Negotiating the climb required me to shift my weight constantly, seeking hand and foot holds on both sides of the fault. I pumped hard with my arms, pulling against the sharp rock.

The silver glint of the anchor came into view, and I called to be lowered without surveying the scene around me. I immediately regretted my oversight, resolving to bring my camera to the top on the next climb.

Nick was coming off the corner when Sam and I wandered over. The sky was clear and endless above his head, strikingly beautiful against the bright yellow leaves of a nearby tree.

The route was deceptively difficult, hard despite the help provided by the square intersection of two sections of rock. The top of the pitch was slightly past vertical, demanding repeat pull-ups to make the anchor. Despite a year of climbing, I hadn’t yet learned to optimize my footholds, and my arms were paying the price.

Standing on a ledge at the top, I turned to take a picture, pulling my small digital camera from its holster. The trees went forever, dappled with sunlight in a two-hundred degree panorama. My leg vibrated against the rock as I recorded the scene, my muscles refusing to relax on my high perch.

Directly ahead, the backside of the Trapps was silhouetted against the clouds, a small depression indicating the path of Route 44 through the Shawnagunks. We'd left behind every sign of man's influence, save this notch.

John set a new anchor thirty feet left of our second climb.

From ten feet back, the face had a single, lonely crack and no discernable footholds. I walked up to the rock, unbelieving. Sure enough, a climb materialized—a ridge on the right, a skinny foothold on the left, and a long reach to safety.

Sam and I stood at the bottom, choreographing every move, positive that we were looking at the hardest climb of the day.

She pushed her hands into the crack, making her first move toward the top. Ironically, the penalty for a fall is higher when the climber is closer to the ground—due to rope stretch, a three-foot drop could result in a broken ankle.

She fell on her second move, hitting the ground feet-first and unhurt. We went over the sequence again, and Sam climbed. She cleared the second move, planting her right foot on an all-day ledge to the right of the crack. Knuckle-deep, she pulled upward.

Her foot slipped off a tenuous left-foot hold, and gravity took over. Weighting the rope, she leaned back from the face and pressed her back against a tree, relieving the accumulated strain on her arms and legs.

The third move beat her several times, each attempt forcing her to clamor into position for the difficult reach once again. Frustrated, she leaned against the tree, ripping her jacket off and staring intently at the rock.

She cranked through the opening moves on her fourth attempt, finding a new handhold slightly higher than her last elevation. A juggy right hand, the hold boosted her up to the first ledge and a long-awaited rest.

The unnamed route was unrelenting. Sparse holds required Sam to crack-climb, a type of climbing her amorphous slippers weren’t made to handle. Noticing the truncated corner configuration of the rock, I suggested she perform a layback, pinning her feet to the left-hand face with her arms fully extended.

This did the trick. Sam pulled through the rest of the lengthy route, plodding through ten meters of energy-sapping ascent. She grunted as she climbed, her exclamations a product of extreme exertion.

On the ground, she shook her hands out, angry at the difficulty of the climb.

Ten minutes later I attempted it, failing in many of the same spots. The first four moves drained my pulling power as I grabbed for the ledge over and over again. The layback reduced my already-fatigued arms to a mass of quivering tendons, my grip junked by the sharp crystals inside the crack. Groaning and grunting, I made the anchor, five or six falls marring the attempt.

My knuckles bleeding, I proposed we name the route. This honor is typically reserved for the first person to complete a pitch, but I’ve never been one to stand on decorum.

The sequence of events drove the nomenclature—“Tree Lean and Groan” was born. Nine days after the experience, my knuckles still bear the marks of that climb, pink and raw across the back of my hand.

Nick beat the hell out of "Tree Lean". He is enormous for a rock climber, tipping the scales at over 200 pounds. Despite his size, Nick has tons of strength, and the prolonged layback suited his abilities perfectly.

With almost no hesitation, Nick cranked up the route, topping out in half the time it had taken Samantha and I. With a mixture of awe and envy, I cheered Nick's tremendous effort, clapping as John lowered him to the ground.

We finished our adventure in The Lost City with an easy climb, scaling a cold corner of the face with minimal effort, enjoying a respite from the mental and physical trials of the day's earlier climbs.

Sam and I packed our ropes and slings, lingering to watch a young German woman attempt a difficult climb. She moved gracefully up the slick rock, holding onto thin air as she flew upward. Her route was easily a 5.10, far beyond our abilities.

My trance was broken as she fell, her belay rope snapping taut in the cold October dusk. We turned to leave, slinging on our packs for the hike back to civilization.

I concentrated on the boulders as we descended from the cliff, scrambling over and around mountains of fallen rock. It felt wrong to leave such a beautiful place--golden trees and a gorgeous blue sky promised that there would be other days like this, days where everything was perfect.

I moved purposefully but slowly, leaving The Lost City only out of necessity. Eventually the scree gave way to open forest, and we joined Nick, John, and Marcia on King's Lane.

We crossed the rushing stream, marking our passage from the dry highlands to the soggy wetland, stepping quickly across the wet stones. We moved single-file along the man-made catwalk, finally exiting to the parking lot at the base of the High Peter's Kill trail.

The weekend was epic, spanning twelve pitches over two days. I felt out of place as we drove east, the beauty of the Shawangunks giving way to the Berkshires giving way to concrete and gleaming metal. The hills receded as we approached the coast, zipping through the suburban enclaves of Wellesley and Newton, the wild plan of nature turning to the carefully-constructed schematics of man.

Reclining in a state of near-sleep, it struck me that I was fortunate to have such friends, folks who knew about the truly important places, places where time is only as important as your next adventure.

That night I fell asleep with a smile on my face, exhausted and elated from our journey. Crossfit was next on the agenda, and 4:30 promised to come quickly.

Go faster!

Ratings and names from the Peter's Kill area courtesy of "Peter's Kill Climbing Guide" by Robert Wilson and Jennifer Sauer. The Lost City is a figment of my imagination, and does not in fact exist. Looking for it is a waste of time, much like yoga or anything involving a Swiss ball.