Climb High

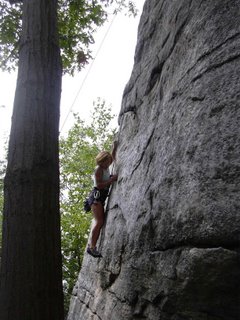

Every once in a while, you see something that’s more beautiful than anything you’ve ever seen before. The Northern Lights over New Hampshire. My first night game at Fenway. The Shawangunk Mountains.

All beautiful places, full of light and texture. Of course, they didn’t let me play at Fenway, and I was eleven the last time I saw the Northern Lights. Beauty is ephemeral, and I have a new favorite.

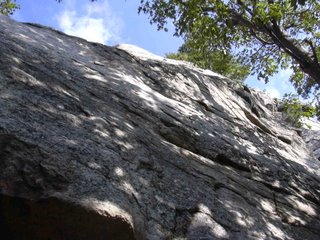

To the untrained eye, the Gunks aren’t especially special. They pale in elevation to the Rockies, and the greenery isn’t anywhere near as verdant as the rain forests of the Pacific Northwest. Yet when we pulled into the base of the Mohunk Reservation, I was enthralled.

A rock they call the Near Trapps looms over a picturesque and under-populated valley, reflecting the sun and crying out to be climbed. If you can rip your gaze away from the cliff, you can see all the way to the horizon. It’s enough to make you want to grow a beard and call in dead.

“Sorry, boss…I mean, um…Mrs. Garcia. Jon died in a horrible accident. Funeral? No, no funeral. He wanted it that way. No, this isn’t Jon. Yes, I know we sound alike…”

We came to climb, so I was pretty surprised when we walked up the mountain away from the Near Trapps. In my trance-like state, I’d failed to notice an equally impressive cliff to my left. There is a limited supply of climbable rock on this Earth, and the Gunks seem to have negotiated an unfair share.

We walked away from the base, tight-roping dangerously close to turnpike traffic. We made a sharp right up a gravel ramp, turning onto an incredibly well-maintained trail. At 9:00 a.m. on a Wednesday, foot traffic was pretty scarce, and the park ranger looked awfully bored as Marcia paid the access fee, using the bed box of an abused pickup truck to fill out the necessary forms.

John led us down the trail, past a thousand feet of perfect rock. I was staring out into the valley, wondering why we hadn’t stopped, when our leader cut left through the woods.

Evidently, we weren’t high enough yet.

Lugging three ropes, all our gear, and enough water to satisfy a dehydrated elephant, we climbed to the base of Twin Oaks. The climb was a 5.3, but I was about to be handicapped.

On our walk, I wondered how one goes about securing top-ropes to a cliff with no obvious means of access. To date, I’d only climbed in two places, both of which allow the climber to walk to the top, place anchors, and walk back down.

John answered my unspoken question with a question.

“Who wants to help me out?”

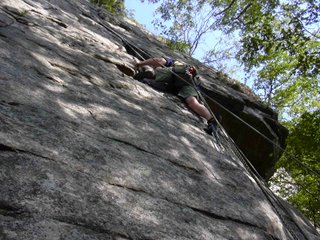

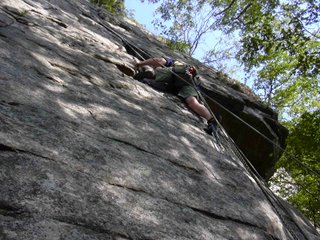

“I’ll do it.” I volunteer for vague assignments awfully easily. John led the climb, placing protection in a wandering vertical crack, clipping in his belay rope as he went. When he topped out, he placed an anchor and sent the loose end of the rope down for me to tie into.

My assignment: climb Twin Oaks with two ropes tied to my harness and a full rack of slings and carabiners looped around my chest. Secure two additional top ropes, and rappel back down. No sweat.

As I took my first tentative holds, I thought of the irony of dragging two ropes behind me. They functioned exactly like the chains on my

AF bar, weighing more and more as I got higher and higher. This was going to be fun.

I was juiced with adrenaline as I scaled the face. My body was unaware of the safety afforded me by my belayer on the ground as I moved upward, but I had the advantage of being absolutely fresh and excited at the prospect of a quick rappel.

I made the top, meeting John and setting one of our three anchors. Satisfied with the state of things, I clipped in for the rappel. Both sides of the rope passed through my belay plate and secured with a locking carabiner, I moved toward the edge.

The down-rock end of the rope was in my left hand, serving as a brake as I stepped backward off the top. A few seconds later I was on the ground, where Nick, Sammy, and Marcia were waiting for the opportunity to climb.

Rock climbing requires a lot of skills that I don't have. Balance, agility, coordination, and the ability to plan for the future are all required. Strength and power take a backseat, the lonely stepchildren on the journey to the top.

As Nick and Marcia climbed Cedar Locks, a 5.5 crack climb, Sam and I messed around on the first pitch of Madame G's, a route that begins with an intricate overhang. Negotiating overhangs requires tremendous pulling power and flawless technique.

Pulling power I've got. Technique--not so much. I had failed three times when Sam joined in the effort. She gave it one shot, and then quickly moved to the right, where the route actually starts.

She's not as stubborn than I am.

We abandoned the overhang and climbed the 5.4 pitch. I concentrated on foot placement and balance as I moved up the rock. I repeated the climb three times, each time finding it easier and easier.

Like

Crossfit, rock climbing demands mastery of new skills. Making the climb means nothing if you don't learn something along the way. You can muscle your way up a face, but the effort looks amateur next to the climbing of a graceful veteran.

John Knight has been climbing for at least several decades. He flies up faces that vex me, and he does it with style. If you put the two of us in a foot race, I'd win. In rock climbing, he will always be my superior.

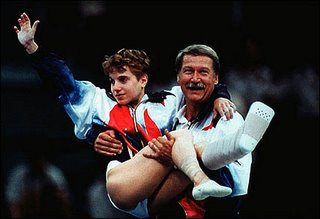

The reason is simple. Developing speed, strength, and power requires relatively little. Train hard, using the right program, and virtually anyone can become quick and strong. On the other hand, developing skill requires extensive practice.

"...improvements in endurance, stamina, strength, and flexibility come about through training. Training refers to activity that improves performance through a measurable organic change in the body. By contrast, improvements in coordination, agility, balance, and accuracy come about through practice. Practice refers to activity that improves performance through a change in the nervous system..."-Crossfit Journal, Number Two.

I have the former skill-set, John the latter. In my own experience, acquiring coordination, agility, and balance requires a greater time commitment that achieving endurance, stamina, strength, and flexibility, but both skill-sets are necessary to achieve our end goal. According to the same Crossfit Journal:

"Power and speed are adaptations of both training and practice."Practice we would. We hit two more climbs on Wednesday, scaling Hyjek's Horror and the first pitch of Columbia. Both were beyond my abilities, coming in at 5.8(-) and 5.7, respectively. Nonetheless, I got great practice on some new skills, including some hand and foot crack jamming.

We left the Reservation tired and hungry. Several beers and one great meal later, we turned in for the night.

The next morning, we retraced our steps up the side of the Mountain, stopping on the wide gravel path by the entrance. John and Marcia set up the ropes as I waited with Nick and Sam. I'd spent the previous evening at the hotel, pouring over climbing magazines from the mid-80s, drawing inspiration from the feats of men who were now becoming fathers and grandfathers. They were frozen in time, wearing garish tights, and clinging steadfast to impossibly tiny holds. They were my heroes for today, and I contemplated the images they'd left as I waited to climb.

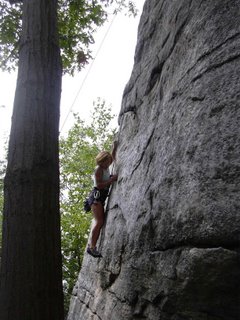

A new skill reared its head as Sammy and I set up on Black Fly, a twisting 5.5 that begins with a layback. Sam instinctively mastered the move, climbing the 90-degree corner with arm tension and a powerful grip.

I had slightly more trouble. I tried the layback three times, failing with each attempt. I walked away, disheartened.

As I watched Nick climb the Brat, I thought about what I was doing. I had quit, and I hadn't made the apex. It wouldn't stand.

I tied in, and jammed my hands into the finger crack at the base of Black Fly. With Sam coaching, I threw my left foot against the wall, and then my right. Arms fully extended, I inched my way up the crack, walking upward. Ecstatic, I made the top and reached upward for the final move to the main face.

One by one, I watched John and Marcia master Handy Andy (5.7) and the Brat (5.6), each climb proving too hard for me. I almost made the anchor on the Brat, but failed as my right calf filled with lactic acid, refusing to move.

At this point in the game, failure and success were relative. I had succeeded in learning several new skills, and I was scaling faces that would have made me feel foolish at the beginning of the summer.

Now we were having fun.

While Sam and I played on The Brat, John set up a climb in the deep recesses of the crag. Easy Keyhole was a 5.2, but it gave us exposure to a type of climb we'd never seen. Straddling car-sized gaps in the rock, Sammy and I climbed up the face, pausing to negotiate a roof three-quarters of the way up.

What the climb lacked in difficulty, it made up for with novelty. The top contained an off-route overhang that demanded my attention. I spent fifteen minutes trying to pull my way over the three foot obstacle, scraping my back and hands on the sharp detrius of several thousand years. I didn't make it, but I gave it a heck of an effort.

Worn from two days of hard gripping and intense focus, I settled in to watch Marcia negotiate Handy Andy. She has outstanding strength and a ceaseless dedication to becoming a better climber. On rock, Marcia is a joy to watch.

As the sun filtered through the trees, we moved to Red Cabbage, the hardest climb of the day at 5.9. I observed as John gave a silent tutorial on economical climbing. He moves with certainty, never pawing at the rock or straining his movements. His talent is borne of patience and practice, and it's worth emulating.

Red Cabbage is reminiscent of an old castle wall. Although my exposure to castles comes solely through crappy Sean Connery movies, the block-like structure of the face brought me back to older times.

Following John's great climb, Samantha gave it hell. She made the anchor after three falls, leaving everything on the wall. She kept at it long after a lesser woman would have given up. When she reached the ground her hands were too smoked to pull her safety knot apart.

I got a final opportunity to rappel on the Mohunk Reservation, cleaning the anchor from the top of Red Cabbage. I let long lengths of rope zip through my brake hand, bounding off the face and catching myself with a controlled knee bend. We had climbed for two days, and they'd gone by like a ten-second rappel.

We packed up and wandered back to the base area, spent and ready for a few more beers.

The Gunks are gorgeous, and they'll be the most beautiful place in my mind until something else takes the throne. Learning new skills in an idyllic setting with great friends is about as good as it gets.

I might find something more beautiful, but I have a feeling it might be a while.

Go faster!

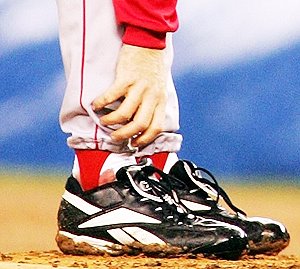

Picture of Kerri Strug courtesy of Herald-Sun.com. Shilling's ankle courtesy of Si.com. Stop by tomorrow for the first look at this Sunday's Again Faster Weekend Workout. It'll be good. I promise.

Picture of Kerri Strug courtesy of Herald-Sun.com. Shilling's ankle courtesy of Si.com. Stop by tomorrow for the first look at this Sunday's Again Faster Weekend Workout. It'll be good. I promise.