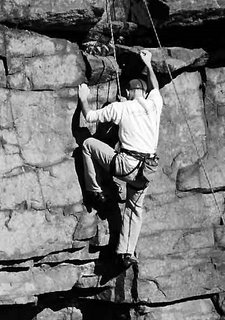

I went to the Quincy Quarry with Sam, her family, and rock-climber/all-around good guy John Knight on Sunday. I hadn't climbed anything in about 10 years, so this promised to be entertaining.

I went to the Quincy Quarry with Sam, her family, and rock-climber/all-around good guy John Knight on Sunday. I hadn't climbed anything in about 10 years, so this promised to be entertaining.It was a gorgeous day--blue sky, hot sun, and good people. I made nice with my buddy SPF 50.

I borrowed a climbing harness from John. I strapped it on, making sure the belt passed through the buckle twice. The rock shoes he lent me were one step away from an Roman-era torture device, but I managed to cram them on.

John taught me basic manners first. The rules are brief. He told me not to step on the rope.

We practiced the question-and-answer sequence that proceeds every climb. The climber and the belayer go through this sequence to ensure the climber's safety.

A little background: The belayer is the person responsible for making sure you don't plummet off a wall. They control the safety rope. It runs through their harness and the belay device, to an anchor at the top of the wall, and back to the climber's harness. As the climber climbs, the belayer takes up the slack, ensuring the climber won't fall too far if he/she falls off the wall.

"Am I on belay?"

The climber initiates the sequence, since he/she is the one taking the risk. The climber is asking the belayer if the belay setup is in order.

"You're on belay."

"Climbing."

"Climb away."

At this point, the climber is headed up the rock, and the belayer is paying close attention, making sure there isn't too much slack in the rope.

Sam and John went through the verbal sequence a couple of times for my benefit, and then showed me how to hook up to the rope.

A figure-eight knot is tied in the rope about two feet from the end. The climber threads the end through his harness, and then ties the tail through the figure-eight. This is a complicated knot, but it's easy to tie. The tail follows the contours of the existing knot, forming a second figure-eight, parallel to the first.

The remaining rope is looped around the upper line twice, and then passed through the loops, again parallel to the line. The climber is secure.

We started on the practice wall. This unimposing face is about 15 degrees less than vertical, littered with deep holds. John belayed for me on my first attempt.

Getting up the practice wall was easy, even for me. A forgiving slope dominates the bottom of the wall, while deep horizontal fissures make the top half negotiable. It got significantly more entertaining when it was time to come back down.

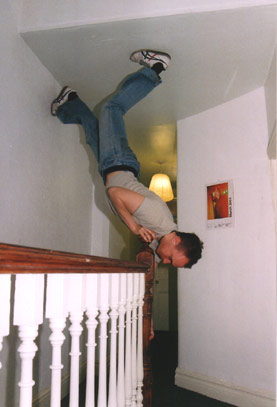

Rappelling is the method of choice. The belayer lets the rope out slowly while the climber walks backward down the wall. John told me to put all my weight on the harness. He didn't tell me to walk backward.

I dutifully did as I was told, slamming my ass against the rock. Evidently, moving your feet helps with rappelling. I live to impress.

I think I heard Sammy giggling.

It is not intuitive to hold yourself perpendicular to a vertical wall, and it took a little practice to keep my feet under me as I walked down the wall. My ego beat me to the bottom.

Back on the horizontal, Sammy and John switched the belay, and I gave it another shot. Up and down, steady as she goes.

Nick and Marcia showed up with Sam's harness and more than a little climbing experience between them. While I was demonstrating my athletic prowess to Samantha, John had setup two more ropes closer to the Quarry entrance.

I watched as Nick and Sam took turns climbing a wall that looked coated in Teflon. They both climbed confidently and quickly. After fifteen minutes, it was my turn.

I got about 20 feet up, and then I was stuck. Nowhere to run, nowhere to hide. My patient surveying turned into frustration. I contemplated the state of the universe for ten minutes and came down. I thanked Sam for the belay, and resumed my role as spectator.

When John finished his first climb, he took me back to the practice wall. It turns out I needed a little more practice.

He had me climb halfway up the wall, and then descend. Instead of rappelling, I climbed downward. This exercise was meant to help me choose good foot-holds. According to John, rock climbing is not about upper body strength. Using the power of the legs gets the climber to the top.

By descending, I had to find a place to put my feet before I went further. Otherwise, I'd just fall off the wall.

The practice restored my confidence. I rested, alternating between the sun and the shade, watching my friends climb the quarry walls.

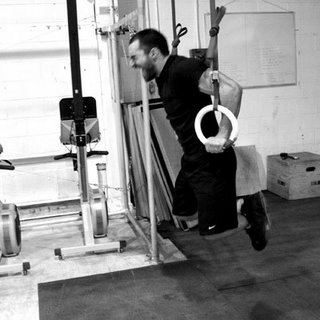

Nick's style is pure power. Grab and pull. Grab and pull. He's quick and strong, and he climbs just like he does everything else. With a lot of grunting. Nonetheless, his strength is really impressive.

Sam is a good climber. She seemed to manufacture holds out of nothing. I watched, mesmerized, as she ascended the wall gracefully and quickly. I only saw her get stuck once, and it lasted all of five minutes.

John dances up the wall, with none of the effort that characterizes my climbing. He moves fluidly and quickly. His style is understated, marked with extreme competence.

Watching them climb helped me mentally prepare for my next attempt. It came at the end of the day, on the highest wall in the Quarry. This wall is vertical and imposing. It definitely wasn't the practice wall.

I watched Nick tackle it--grab and pull, grab and pull.

John off-handedly told me I should give it a shot. Ummm...okay then. I quietly focused on Nick's holds and moves, knowing I'd have to replicate them.

Nick made the top.

I tied in, using the knot Sammy had shown me earlier in the day. For the first time, I managed to get it right without assistance.

"Am I on belay?"

"On belay", John answered.

"Climbing."

"Climb away."

Holy sh*t. This wall is all kinds of vertical. I jumped for the first hold, pulling myself up to a ledge about 7 feet above the ground. Another hold just above my head. Another pullup got me there. I realized that I was ignoring John's advice about finding my feet first.

I made it about three-quarters of the way up the wall. After a particularly difficult move, I rested against the face, catching my breath. 20 feet to go. I found my next foot-hold, and dug my right hand into a crack. I pulled my arms together, pec-dec style, and weighted my up-rock foot.

Buh-bye.

I fell off the rock, and John caught me. So that's what that rope is for.

Back on the face, my legs started shaking. Violently. It turns out no one had told my lower body that I wasn't scared. After 3 seconds of deep reflection, I told John I was coming down.

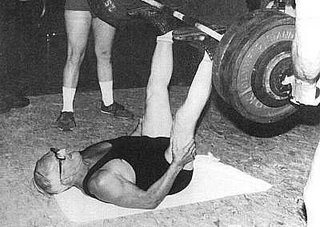

My day was over, and I'd been beaten by two different rock walls. They say humility is a virtue. I'd managed the practice wall a couple of times--my fourth climb ever was a 5.8. You can see the route in the first picture from "Monsters of Rock"--it's just to the left of the guy in yellow.

Sammy told me she was impressed, then managed to climb the wall that had just stomped on my self-esteem.

As I watched, I realized what a beautiful thing rock climbing is. We were climbing something that was not meant to be climbed, using our bodies as a means to scale vertical faces. Done masterfully, rock climbing is a unique combination of spatial awarness, power, and grace.

It's also a hell of a good time. I'll be back. Next time the rock won't win.